1

Application No 23390/94

R ACHEL HORSHAM V THE UNITED KINGDOM

In response to the letter dated 10 January 1995 from the United Kingdom I Rachel Horsham hereby present the following observations, in relation to those received, by you, from the United Kingdom.

In these observations I shall proceed through the four parts as set out by the United Kingdom.

PART 1 RELEVANT FACTS

In paragraph 1.1 The Deputy Advisor and Agent for the British Government states, "Without prejudice to any of the legal issues in these proceedings, the United Kingdom will refer to the applicant as She".

My legal status as such is that of a woman and declared legally so by a competent court of law, with medical backing and can be no other than that. Any attempt by the Authorities of the United Kingdom to declare me as anything other, is prejudice to my legal standing and rights.

PART II. RELEVANT DOMESTIC LAW AND PRACTICE

2. In paraqraph 2.1 The statement noting Cossey v United Kingdom (Judgement the Court, 27 September I990, Series No.I84, para. 16 of the Judgement) is of no avail or relevance to my case, in that. The English system of Dead Poll, concerning change of forename is not legally recognised outside of the United Kingdom. Change of name by Deed Poll in the United Kingdom is purely an action between a solicitor and client with no Court action needed, therefore unrecognised within the law.

As I have stated previously. In the documents signed on the 3/12/93, that were sent to you on the same day, I repeat to you what is contained on page 19 under the heading legal status. "I visited the British Consulate in Amsterdam to enquire over a new passport to reflect my status as a woman. During an interview with the Consul, I was informed that it was not possible to be issued with a new passport reflecting my currant status, at the time. Nor would they accept a letter of Deed Poll from a Solicitor for a change of forenames. Their reasoning. That the issuing of passports to transsexuals in the United Kingdom, showing their female status, on production of a letter of Deed Poll from a Solicitor, and a letter of acknowledgement from a qualified doctor, that the bearer was a transsexual, was not legal outside of the United Kingdom."

In my case my change of forename eventually had to be done through civil law proceedings. Which included a legal change to my sex status, originally recorded as male now recorded as female, with medical advice and knowledge of my situation given to the court, under Art 29a to d of the Burgerlijk Wetboek of the Netherlands.

2 3. In para 2.2 Their statement that my change of name was recorded on my passport, issued by the United Kingdom Consulate in Amsterdam, is a fact. But they fail to state, that it could not be done through a letter of Deed Poll, as Deed Poll is not recognised outside of the United Kingdom. That it was issued after production of the Court proceedings here. The Consul noting that the court proceedings, also in their verdict, demanded the enrolment of my birth certificate into the registers here in the Netherlands, and the changing of my sex status from male to female.

4. In para 2.3. Concerning marriage. Again the Cossey case is of no avail in regards to my case. The information that the British Government had given the Court, in the Cossey case, was misleading, with the exception, that in English law, marriage is defined as the voluntary union between one man and one woman. What was misleading was their definition of how a person's sex is determined by, chromosomal, gonadal and genital, being congruent, without any regards to surgical intervention. It has been known now for some time that a persons sex cannot be defined solely on such criteria, and this has been established already by medical research. Their use of Corbett is also of no avail in my case, and should never have been used in the Cossey or the previous case of Rees.

As I have already stated in the document that were sent to you on the 3rd December 1993, the Corbett case cannot be held valid.In that, Judge Ormrod went beyond his powers by going into the Alternative and by doing so broke the Rules of the Supreme Court, RSC, and thereby creating a situation of Ultra Verus and creating a situation of Orbita Dicta which made his final judgement invalid. If he had kept to the petition alone, and demanded to see the birth certificates of the petitioner Arthur Corbett and the respondent, April Ashley. He would have seen immediately that Arthur Corbett was male, and that April Ashley was in reality still George Jamieson male, with no amendment on the birth certificate to show any other. From that point Judge Ormrod could only make one decision, that the marriage was null and void. But instead he went into the alternative, of which he had no right to do. In doing so the realities of the case became very clear, it was deliberate. At one point he stated, p. 47 line G of the Corbett case, "It appears to be the first occasion on which a court has been called on to decide the sex of an individual and consequently there is no authority, which is directly to point". He had not been called upon to do this, he had only been called upon to grant a decree of nullity on the ground that April Ashley was of the male sex at the time of the ceremony. Which was true and his decision should have been made on the evidence of the birth certificates.

Neither did Ormrod have the medical knowledge to make a legal decree that a person's sex was to be determined solely by chromosomal, gonadal, and genital, and that a persons sex was fixed at birth, without regard to surgical intervention.

Throughout the case he relied solely on medical evidence of two people, namely, Dr Randell and Prof Dewhurst, who were of the opinion that for them April Ashley was a homosexual, and disregarded the evidence of another seven medical

3.

Witnesses, who were of the opposite opinion, in that April Ashley was a transsexual or a person of Inter-sex, and should be legally regarded as a woman.

Also in the documents that were sent to you on the 3rd December 1993, was a copy of the research reports from Prof L.J.G. Gooren, of the Gender Centre at the Free University Hospital of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. This centre is the only one of its kind in Europe, and it is also the leading research centre that has researched into the determining of a persons sex, to a greater extent than anywhere else.

On page two, under, SUMMARY, it reads:

Transsexualism remains an enigmatic problem to biologists. It defies the "naturalness" of being a man or a woman. In the past century it has become clear that the differentiation process of becoming a man or a woman is a multi-step process. At each step there is a bipotentiality to develop in either male or female direction. Further, each step has a window of time, a critical phase for its development. For times immemorial it has been assumed that the sexual differentiation process is completed with the formation of the external genitalia, which constitutes the criterion for sex assignment immediately after birth. Over the last decades it has become apparent that the formation of the external genitalia is not the final step in the process of sexual differentiation but also the brain undergoes a sexual differentiation, which in the human occurs after birth. Though the information is not definitive there is now evidence to believe that in transsexuals the sexual differentiation process of the brain has not followed the course anticipated of the preceding criteria of sex (chromosomal, gonadal and genital) and has become cross-sex differentiated. Sex assignment at birth by the criterion of the external genitalia is a statistically reliable prognosticator of future brain sexual differentiation. For the exceptions in whom brain sexual differentiation has not followed the path prognosticated by the nature of the external genitalia, i.e. transsexuals, the law must make provision.

Again on page 16, 17 and 18, under, SUMMARY OF BIOLOGICAL SEX DIFFERENTION AND ITS RELEVANCE TO TRANSSEXUALISM, MEDICINE AND LAW

It has become clear that the differentiation process of becoming a man or a woman is a multi-step process with for each step a window of time critical phase. Once this phase has passed there is no backtracking. With the fusion of an ovum and sperm, the chromosomal pattern becomes established: usually 46 XY or 46 XX, but other configurations do occur. The most well known are 47XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) and 45, X (Turner syndrome). The differentiation of the gonads takes place in the human foetus between 5-7 weeks of pregnancy. The indifferent, biopotential gonad becomes a testis provided the correct genetic programming is present on the short arm of the Y chromosome. Sometimes this information has been translocated to the X chromosome resulting in a 46 XX man with a reported frequency of about 1: 20,000. A XY chromosomal pattern may result in a development of a female with streak gonads if the "testis determining area' is lacking on the Y chromosome.

4.

When the gonads have become either testis or ovaries (or in rare cases ovotestis), the next stepof the differentiation process is the formation of the internal genitalia. The foetal testis become endocrinologically active and secretes testosterone and Mullerian inhibiting factor leading to involution of the ducts of Wolff. The ovaries are endocrinologically quiescent. The ducts of Wolff regress in the absence of testosterone while in the absence of Mullerian inhibiting factor the ducts of Muller differentiate into female internal genitalia. The following step is the formation of external genitalia, obeying to the same paradigm: male external genitalia in the presence of testosterone (provided it is metabolised to 5 alpha-dihydrotestosterone) and other androgenic hormones. There are two classical syndromes of which the errors in sexual differentiation occur in this phase: the androgen insensitivity (AIS) and the congenital virilising adrenal hyperplasia (CVAH). The essence of the AIS is that all body cells lack androgen receptors. It has only been found to occur in 46 XY subjects with testes are born and raised as girls. A similar clinical presentation, have those 46 XY testis bearing subjects who have an enzymatic block in the production of testosterone. In the CVAH there is an abnormal amount of androgen production of the adrenal (On the basis of an enzyme defect in the cortisol synthesis). The much higher than normal androgen production leads in an affected 46 XX foetus with ovaries to a male type of differentiation of the Wolffian ducts and the external genitalia; in other words these 46 XX ovary baring subjects are born with a penis and a scrotum and raised as boys. The above two clinical syndromes can be complete or incomplete. Apart from the two above classical syndromes there are more errors in the sexual differentiation process of the internal and external genitalia, leading to male genitalia in foetuses with a 46 XX chromosomal pattern and ovaries and to female external genitalia in foetuses with a 46 XY pattern and testes. More often ambiguity of the external genitalia is the result of a faulty sexual differentiation process of the external genitalia. The formation of the genitalia is concluded by the 16-17th week of gestation. Since times immemorial mankind has assigned its offspring to the male or female sex by the criterion of the appearance of the external genitalia without encountering great problems. This practice infers, on the basis of a single glance, that all criteria of sexual differentiation (chromosomal pattern, nature of gonads and of internal genitalia) in their entirety are either masculine or feminine. This inference appears to be justified in the vast majority of newborns but there is no certainty that the other criteria of the sex are congruent with the appearance of the external genitalia. Abiding by the principle of assigning newborn to the male or female sex by the criterion of the appearance of the external genitalia, this practice will inevitably produce that some subjects will be legally registered as male while their other criteria of sex (chromosomal pattern, gonads, internal genitalia) are discordant with those of the average male and vice versa will be the case with persons registered as females.

5.

Even more complex are those cases of newborns with ambiguous genitalia. The homespun wisdom of the medically unsophisticated confronted with such newborn, guided them to assign the baby to the sex to which it most resembled in genital appearance. After the advent of medical technology to determine the nature of the chromosomal pattern and the gonads and internal genitalia, this practice was reconsidered. Starting with Klebs in 1876 it was assumed that microscopic examination of the gonad (testis or ovary or ovotestis) would provide a secure criterion as to the true sex of the newborn. The introduction of techniques of chromosome determination tempted scientists to adopt a chromosomal criterion instead. It is evident that these approaches were teleological in nature, in other words they tried to read from the chromosomal pattern and the gonadal tissue what nature's original 'intentions' had been with the subject involved. These medical procedures turned out to be disastrous for the subjec. As can be understood from the information on sexual given above, such procedures leads for instance to assignment to the male sex with 46 XY chromosome pattern and/or testes while this subject has external female genitalia which cannot satisfactorily be surgically reconstructed to male genitalia. It is not difficult to imagine what misery this approach must produce for the subject involved with regard to his functioning as a male in all its aspects.

It has been the pioneering work of Money and Wilkins mentioned earlier, in children with ambiguous genitalia that has led to a new style of clinical decision making on sex assignment in the newborn. The decision on sex assignment is in modern medicine primarily guided by the nature of the external genitalia and/or how well they lend themselves to surgical reconstruction in conformity with the sex the newborn is to be assigned to. Preponderant in the decision is the clinically well founded expectation of the sex role in which the newborn will genitally function best in childhood and adult life, privately as well as socially and sexually. Future fertility must be considered but is not predominant, since it may be totally at odds with the genital status (for instance in a subject that has a vulva and a vagina and fertile testes).

It is clear that the above clinical practice gives high priority to the expected future genital functioning of the newborn with a substantial disregard of the chromosomal pattern and of the gonod. Most lega1 systems accept that in the case of newborns with ambiguous genitalia, sex assignment is executed on the basis of expertise. It is evident from the above that medicine is unable to determine sex by a single criterion, like chromosomal gonada1 and genital characteristics. All variables of sex are usually concordant with another but they are capable of being discordant. For the healthy psychomedical development of a child, if not it as doomed to become a queer person, it is,

an exigency that it is assigned to either the male or the female sex. This assignment, is usually made by parents, or caretakers on the basis of the appearance of the external genitalia.

6.

The civil registration as female will be in agreement with the assignment of the parents/caretakers in cases of ambiguous genitalia or with the medical expert advice in cases of genital ambiguity. Consequently, civil registration is subject to the same uncertain arbitrary determination of sex as the medical profession is. Most legal systems have, in times that it was known that sexual differentiation is a stepwise process with several variables, prescribed that civil registration is to be enacted by the criterion of the appearance of the external genitalia.

Though it is no doubt, an expedient practice doing justice to the vast majority of citizens, it must be recognised that it hinges on only one of the variables, one of the criteria of ones sex. From the above arguments it is clear that no single criterion can, psychomedically speaking, satisfactorily define sex and therewith the most widely prevailing legal criterion of sex, that of the external genitalia is scientifically no longer uneqiuvocal.

Another aspect of civil registration as male or female is that it is legally bound to take place within a number of days after birth. The demonstrable sex difference in the brain become only manifest by the age of 3-4 years postnatally. In contrast to lower mammals the process of brain differentiation has no direct relationship with sex hormone action, theoretically leaving room for other agents to direct this differentiation process. Upon examination of a very limited number (three subjects) of male-to-female transsexuals post mortem, their brains showed morphological differences in comparison with non- transsexual controls. Apart from these morphological findings, also testing brain function of transsexuals provided evidence of a cross-sex differentiation of their brains.

The implication of the above scientific insight that the sexual differentiation of the brain occurs after birth is that assignment of a child to the male sex by criterion of the external genitalia is an act of faith. In the reality at every day it is an expedient practice exercised by mankind since time immemorial. Only as few as 1:10, 000 males and 1:30, 000 females (Bakker, van Kesteren, Gooren & Bezemer, 1993) (Tsoi, 1988) will later experience a contradiction between his/her gender identity/role and the actual genital morphology and othe criteria of sex. Consequently like the other variables in sexual differentiation (chromosomal pattern, gonads) the external genitalia are excellent, statistically reliable prognosticators of one's future gender identity/role. By contrast, on the basis of this recent neuroanatomical evidence at is reasonable to require from the law that it makes provisions for those rare individuals in whom the formation of gender identity has not followed the course otherwise so reliably prognosticated by the external genitalia. Denial of this right is a negation of an important piece of scientific information on the process of sexual differentiation of the brain taking place after birth. If a strict and intransigent adherence to the criterion of the appearance of the external genitalia as directive for sex reassignment is observed, it must be

7.

realised that prenatal determinants of sexual differentiation (chromosomal pattern, gonadal characteristics, hormone production) may be at variance with the nature of the external genitalia for sex reassignment is less solid, less unequivocal as it would seem to most legal experts. The validity of this criterion has been superseded by the scientific information that sexual differentiation is not a one point deterministic process, but a succession of steps concordant or discordant with each other. The existing law practice does justice to those newborn in whom all steps are concordant. The less fortunate citizens in whom all these steps have been discordant deserve no less.

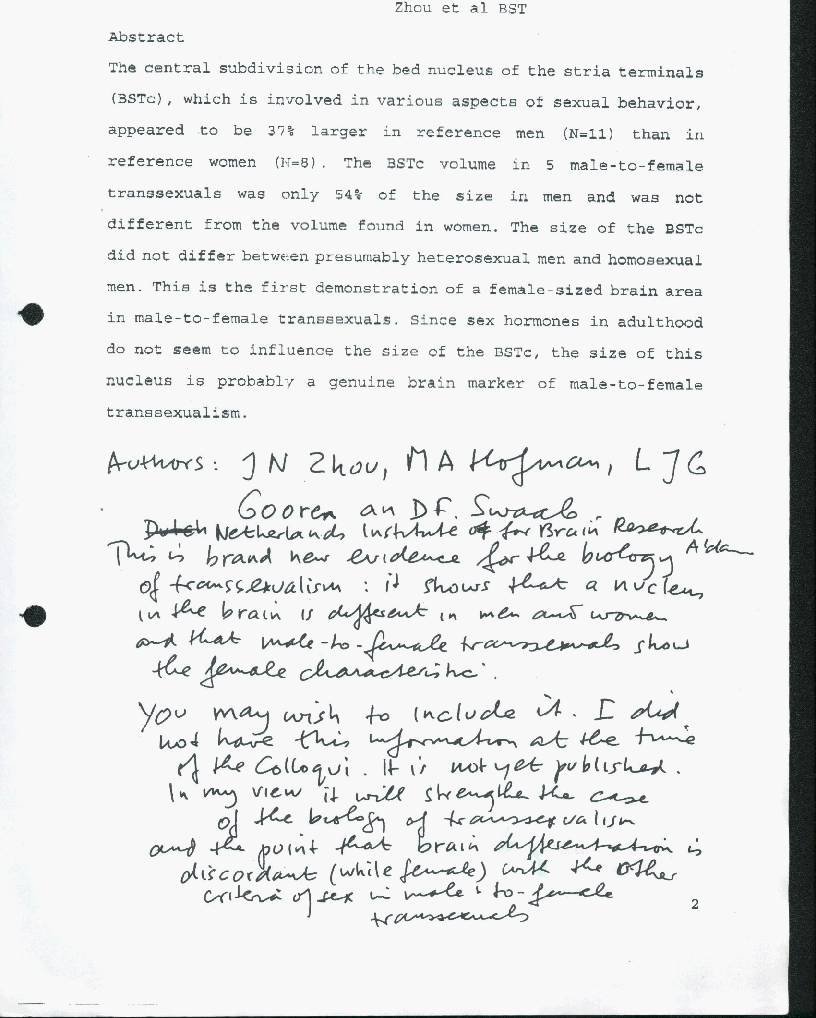

In addition to the above information I now present the latest medical scientific findings that were not available to be presented to the 23rd Colloquy held in Amsterdam in 1993. The following information, as well as the above is attested as true and accurate by Prof. L G J Gooren. It clearly shows that a transsexual is born and it is biological and NOT psychological as stated by the British Government.

ZHOU ET AL BST

The central subdivision of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTc), which is, involved in various, aspects of sexual behaviour appeared to be 37% larger in reference men (N= II) than in reference women (N= 8). The BSTc volume in 5 male-to-female transsexuals was only 54% of the size in men and was not different from the volume found in women. The size of the BSTc did not differ between presumably heterosexual men and homosexual men. This is the first demonstration of a female-sized brain area in male-to-female transsexuals. Since sex hormones in adulthood do not seem to influence the size of the BSTc, the size of this nucleus is probably a genuine brain marker of male-to-female transsexualism.

The authors of this information are. J N Zou, M A Hofmann, L G J Gooren and D F Swaab. From the Netherlands Institute for Brain Research. It clearly shows the point that brain differentiation is discordant (while female) with other criteria of sex in male-to-female transsexuals.

5. Again, In para 2.3 The use of R v Tan (1983) QB 1053 1063H-1064E is of no avail in my case, or was it of any avail in the Cossey and Rees cases. R v Tan was primarily a case concerning prostitution, and that Tan had been surgically operated on previously, the birth certificate showing Tan to have been registered at birth as of the male sex. The use of Corbett in that case using case law to determine if the defendant Tan was to be seen legally as a woman or a man. There had been no amendments made in the birth registers to state that Tan was legally a woman. Therefore using Ormrod's judgement it was decided that Tan was legally a man. In my case I have a legally amended birth certificate, that was ordered by a court at law, within the Law, showing me now as a woman and not a man. Laws that are passed through an Act at Parliament, to be registered in the Law books, are in the ascendancy concerning a person's rights or misdeeds. Whereas case law may be used if no law of the land can be found. In my case the law of the land, being the Netherlands, is in the ascendancy, as opposed to case law.

But there again, in the Tan case, there was an existing Act within the 1953 Births and Deaths Act that did allow Tan to have the birth certificate changed. The fact that Ormrod's judgement in the Corbett case can now be seen as invalid in that he broke the rules of the Supreme Court, creating a situation of Orbita Dicta, also invalidates, to an extent, the judgement in the case of R v Tan.

6. Again, in para. 2.3. The statement that a person who was born male and has undergone reassignment surgery cannot marry a male, clearly shows the British Government having complete contempt for what are known scientific facts. In that a person's genitalia, as seen at birth, cannot be held, as the one reliable factor as to determine for a person's life what their real sex is. This is what Judge Ormrod decided in the Corbett case, and Judge Ormrod did not have the right to make such a decision, as he was not qualified to do so. Nor was he called upon to do so.

As a woman I have the right to marry any man I choose to, and who wishes to marry me. My new birth certificate gives me that right. It is only the United Kingdom who is intransigent in this affair.

7. Again in para 2.3 concerning marriages outside of the United Kingdom, that they accept their validity, providing it satisfies the laws of the country that they took place in.

If they accept such a marriage taking place between a person who in their eyes was registered at birth as a male and later is seen as being female, but with no amendment having been made in the birth register to support this. It must follow that the Law in the United Kingdom must accept that person as being legally a woman. In reality they do not. She would not be recognised legally and socially for purposes where Pensions are concerned neither would she be recognised as a woman, if she found herself to be the victim of rape. She would not be legally recognised as a woman if she were to die suddenly. Her death would be registered as a man. Here we see that not even the dead, are allowed to rest in peace.

I present here an example of this situation. On the 21st of September I sent the first documents of my case to the Commission. In those documents I made a demand for a review of the Cossey case judgement, considering that the Commission did judge in her favour that she had the right to marry a man. The government of the United Kingdom appealed against that decision to the High Court on the grounds, that in their view her case was no different to the Rees case. The High Court upheld the appeal on those grounds in favour of the British Government.

In the following documents I sent to the Commission, dated 3rd of the 12th 1993,was enclosed an Authorization to represent Miss Cossey in my case, which was signed by her.

In August of 1992 Miss Cossey was married to a Mr Finch, a Canadian and British citizen in Montreal.

9.

Before the marriage could take place she had to produce her birth certificate, after which special permission was granted, in view of the fact that she was refused a legal amendment to her birth certificate in the United Kingdom. After this permission was granted and the marriage took place. She is now legally Mrs Finch and living with her husband in Atlanta Georgia, United States of America. She has an official Green Card to live and work in the U S A. Her husband is at present working to obtain his green card. When her husband attains that green card, his wife automatically is placed in that registration. This involves documentation procedures that are involved with the F B I. When this occurs she will have to produce her birth certificate, which will show her as a male, which will cause official problems even though their marriage is legally recognised. They can both return to the United Kingdom, but at a certain level their marriage would not be recognised by certain departments in the United Kingdom, because of the unamended birth certificate. This is interference in their private life, created by the intransigence of the United Kingdom Government.

The same situation would happen with me, as the United Kingdom Government refuse to recognise my new legally amended birth certificate. Which is a step further than Mrs Finch who has no amended birth certificate.

I would point out, that as the United Kingdom Government still recognise the Corbett Judgement, any divorce that might take place in this situation would leave me without any legal rights. The court would say, that according to English law I was born a man and as there is no amendment contained in the Registers in the United Kingdom to show any other than that, an immediate decree of nullity would be granted to the petitioner on the ground. That in the judge's view I was and still am legally a man.

8. I n para 2.4 Concerning BIRTH CERTIFICATES.

Again the United Kingdom areattempting to use the Cossey case, and again I will state that the Cossey case is of no avail in respect of my case. The paragraphs which they have produced, which were taken from the judgement in the Cossey case, are in fact a statement from the court of what they were led to believe by the British Government, in the evidence that was given in the Rees case. Again I stress that the court was mislead by the British Government.

The British Government used the judgement from the Corbett case as an explanation to the court, as to their reasons why the birth certificate could not be changed or amended. As Judge Ormrod stated in his judgement, "what is meant by the word women in the context of a marriage. The criteria must , in my judgement be biological, for even the most extreme cases of transsexualism in a male or the the most severe hormonal imbalance which can exist in a person with male chromosomas, male gonads and male genitalia cannot reproduce a person who is naturally capable of performing the essential role of a woman in marriage. In other words the law should adopt, in the first place, the first three of the doctors criteria i.e. the chromosomal, gonadal and genital tests and if all three are congruent determine the sex for the

10. purpose of marriage accordingly, and ignore any post operative intervention. My conclusion therefore is that the respondent is not a woman for the purpose of marriage but a biological male and has been since birth".

(A comment by Prof L .J Gooren on such a judgement is as follows: "There are many women everywhere in the world (also in the UK) with the Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: they have XY chromosomes, testis, no uterus, but a vagina. They are identified as female at birth and raised as girls. They marry without Judge Ormrod’s consent. What is granted to these women must be granted to persons in a similar situation.")

Again, I stress the Corbett Judgement has no value here. His judgement had no real scientific backing behind it, neither did he have the right to make such a judgement, neither did the British Government have the right to use such a judgement, knowing that there is available scientific evidence to over-rule Ormrod's statement.

9. The content ions that in United Kingdom the birth certificate is a historical document as opposed to other countries. That statement has no factuality in it, it was only used as an excuse as to why they should not amend the birth certificate where necessary, neither is it stated in the Births Act that this is so. Neither can such an excuse be made as to why they should be able to renege on people's human rights.

In the Netherlands a similar situation existed, in that it was not possible to change the stated sex on a birth certificate, neither was it possible to make amendments to it. Until it was decided that the only way, was to make an Act of Parliament that would go into the civil law books, which are additional Acts to the Births Registers Act here, and are now law.

10. Neither are there such restrictions laid down in the 1953 Births and Deaths Act stating how a persons sex was to be determined. This was something that had already been taken taken for granted for a few thousands at years, that it the genitalia protruded it must be male, if the genitalia are inverted it must be female.

11. The Births and Deaths Act of 1953 was an act to consolidate earlier enactments. The Acts are created by parliament and are open to change by Acts passed by parliament. Neither is an individual such as a judge allowed to dictate how the Act itself shall be used. In this parliament is the supreme Lawmaker.

As stated from Halsburys Laws. The Births and Deaths Registration Act 1953. An Act to consolidate certain enactments relating to the Registration of Births and Deaths in England and Wales with corrections and improvements made under the Consolidation of Enactments (Procedure) Act 1949. [14 July 1953]

Sec; 1. PARTICULARS OF BIRTHS TO BE REGISTERED

(1) Subject to the provisions of. this part at this Act, the birth of every child born in England or Wales shall be registered

11. by the Registrar of Births and Deaths for the sub-district in which the child was born by entering in a Register kept for that sub-district such particulars concerning the birth as may be prescribed; and different Registers shall be kept and different particulars may be prescribed for live births and still births respectively.

Provided that, where a [stillborn child is] is found exposed and no information as to the place of birth is available the birth shall be registered by the Registrar of Births and Deaths for the sub-district in which the child is found.

(2) The following persons shall be qualified to give information concerning a birth that is to say-

(a) The father and mother of the child

(b) The occupier of the house in which the child was to the knowledge of that occupier born. (c) Any person present at the birth. (d) Any person having charge of the child

(e) In the case of a stillborn child found exposed the person who found the child.

Sec; 29 CORRECTION OF ERRORS IN REGISTERS

(3) An Error of fact or substance in any such Register may be corrected by entry in the margin (without any alteration of the original entry) by the officer having the custody of the register,..…upon production to him by that person of a statutory declaration setting forth the nature of the error and the true facts of the case made by two qualified informants of the birth or death with reference to which the error has been made, or in default of two qualified informants then by two credible persons having knowledge of the truth of the case.

Sec; 35 OFFENCES RELATING TO THE REGISTERS

If any person commits any of the following offences, that is to say—

(a) if being a Registrar, he refuses or without reasonable cause omits to register any birth or death or particulars concerning which information has been tendered to him by a qualified informant and which he is required by or under this Act to register. He shall be liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding [level 3 on the standard scale]

12. As can be seen above it is possible to have the required amendment placed on the full birth certificate. When a short birth certificate is made from the registers it will only show the persons officially altered sex status, and the new names. When a person then acquires an official identity document, such as a passport, drivers licence etc, the documents have a completely valid legal. But then again the persons newly acquired status can in no way shield them from any legally binding commitments that they were involved in before the change was officially registered.

Neither is it possible for the original entry to be erased and can be found by a third person, providing they know the original name and place of birth and the year. But then the original entry would have no legal validity any more, as the amendment would take legal precedence.

It should also be noted that the Registrar by not registering such new information without reasonable cause is committing an offence. It is clear that it as not a problem connected to the births register or anything in the act itself nor any such excuse as it being a historical document, as the Act itself is subject to repeal by parliamentary Act. The bane of the problem is the Corbett case, which as I have said earlier is invalid and it was contrived to deliberately create this situation.

In the documents that I have already sent can be seen copies of the letters from the OPCS where it was stated that there were no provisions in the registers for an amendment to be entered. Which was a lie, there is, and as such the Registrar has committed an offence under sec; 35 of the Births and Deaths Act. In that the documents I had sent to him were legally valid, medically approved, and he failed to register the amendment as is demanded under sec; 29 p. (3) of the Act.

13. in para 2.5 The representative of the United Kingdom stated that the amendments to the birth certificates, that I had included in my case documents, were carried out under the provisions of the statutes (or its predecessor). This is true, as I have shown here, but the statement (or its predecessor) shows clearly that the United Kingdom are again attempting to mislead the court. The Births and Deaths Act of l953 is as I have stated earlier, a consolidation of the Acts of England and Wales. The certificates I have shown were amended under sec; 29 of the Births and Deaths Act of 1953, and is still in force.

The attempts by the United Kingdom to again use the judgement of the Cossey case as a guide here is of no avail in my case. That judgement came about only through the misleading information the United Kingdom presented to the court.

A person of inter-sex is a transsexuai. The word transsexual was created by Dr Harry Benjamin an Endocrinologist from New York. He created the name as a medical term for the people he found who were suffering from this situation. He realised that such people were sexed wrongly from birth. That was in the 1950s, but why, was a mystery then. Since then the same situation hats been termed as a person of inter-sex, it means the same, but the term transsexual is the most widely common term used.

14. The representative for the United Kingdom states that in none of the incidences was gender reassignment surgery carried out on the people whose certificates were changed. Medically and surgically that is an impossibility. Hormone and surgical treatment had to be carried out, and evidence of that would have been given to the Registrar at the time. On reading of the newspaper article in their annexes, it can clearly be read that Roberta Cowell had to have hormone treatment and surgery, and her statements as to the feelings she had all her life, are exactly what a transsexual feels, no different. She was a transsexual, I should know as I have gone through the same situation. But then newspaper cuttings have no legal validity where the Law is concerned. Neither should a person like Roberta Cowell lose the legality she now has as a woman, and neither should I or any of the other people whose birth certificates that have been shown in this case. They are primary examples to show that the United Kingdom has wilfully mislead the court in Strasbourg in previous cases. (A comment again by

13.

Prof L G J Gooren, this time concerning the newspaper statements by Roberta Cowell, as have been forwarded by the government of the United Kingdom. "Several inter-sexes need hormone and surgery to achieve their status as male or female, there is no essential difference with transsexuals".)

15. They also state that they arc unable to supply information concerning these people, and that such information is private. This is an easy way out, but I do agree that such information is private, but that does not explain why information concerning me should be of a public interest to other people in the United Kingdom or anywhere else in the world, as I am no different.

Again they use the judgement of the Corbett case, and it is invalid. The truth is that if any of the people, whose birth certificates were changed prior to the Corbett judgement attempted to do so after that judgement, they would have been refused. Using the same reasoning that they have mislead the court with in the Rees and Cossey affairs, just as they are attempting to so do in my case.

16. In para 2.6 It is stated that; section 142 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 defines rape as vaginal or anal intercourse and the offence is not dependent on whether the victim is a man or a woman.

Again I accuse the United Kingdom government attempting to mislead the Commission. My enquiries into this particular piece of Legislation they speak of, states, ‘that the definition of rape against a person of the male sex is "forced anal penetration", and the definition of rape against a person of the "female sex is" "forced vaginal penetration". Therefore as they refuse to recognise my legal and lawfully given sex status as a woman, I can be legally raped in the United Kingdom. As an act of rape against me would be "forced vaginal penetration".

Concerning section 142 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994. The 1994 volume of Halsburys Law does not contain anything concerning this Act, which means that it has not been published yet. But it does contain under Criminal Law Vol 12 p.248 under Unnatural Offences section 12 Buggery (I)

It is a felony for a person to commit buggery with an another person or with an animal.

The act of buggery always has been and still is anal intercourse between two men. Rape is an entirely different matter. Under the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1976. Section 1. Meaning of "rape"etc.

(i) For the purposes of section 1 of the Sexual Of fences Act l956 (which relates to rape) a man commits rape if-

(a) He has unlawful intercourse with a woman who at the time at the Intercourse does not consent to it; and

(b) At the time he knows she does not consent to the inter course or he is reckless as to whether she consents to it.

And, references to rape in other enactments (including the following provisions of this Act) shalt be construed accordingly.

(2) It is hereby declared that if at a trial for a rape offence the jury has to consider whether a man believed that a woman was consenting to sexual intercourse, the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for such

14.

a belief is a matter to which the jury is to have regard, in conjunction with any other relevant matters, in considering whether he so believed.

17. It can clearly be seen that if it was put to a jury that the woman was not a woman, but a transsexual and still in the eyes of the law legally a man, it would be considered that the offence would come under buggery or assault. No consideration would be taken that at the time the assailant had unlawful vaginal intercourse and no act of buggery took place.

Again in VOL 12 CRIMINAL LAW p. 686 sec 2 para (3). In subsection (1) of this section "complainant" means a woman upon whom, in a charge for a rape offence to which the trial in question relates, it is alleged that rape was committed, attempted or proposed.

Therefore within English law I can be legally raped and the offence seen within the eyes of the Law as "assault or buggery". In that, within the eyes of the law in the United Kingdom I am considered a man and not a woman even though outside of the United Kingdom I am considered legally a woman. Which in reality I am.

18. In para 2.7 Nothing in this observation states that in the circumstances of serving a term of imprisonment in the United Kingdom that I would not be sent to a prison for men.

They state, "that in some cases post-operative transsexuals have been placed in a prison catering for the sex which accords with their new social status". In their statement, "post-operative transsexuals with their new social status", is very clear that the Government of the United Kingdom refuse to recognise such a persons legal status. There is a distinct difference between, a person's "social and legal status". Further they state, "consideration is given to the individual circumstances of each case of a transsexual sent to prison in order to determine what would be most appropriate".

When consideration as based on non recognition of a persons legal sex status and only on social status ,then the outcome is inevitable that such a person could be sent to a prison for men.

For example, a male transvestite is legally a man, but they can be socially regarded in the female role. On the other hand a Transsexual is a person who is born wrong, where the sex differentiation process went wrong, and as such is a person of inter-sex. After treatment and corrective surgery, that person can no longer be regarded as a transsexual, but of the sex they were biologically meant to be, and must be given that legal recognition.

I can see nothing in the statements put forward by the United Kingdom, that I would not be incarcerated in a prison for men, and that is very clear, that again they refuse to accept my legal status as a woman.

19. In para; 2.8 Concerning, social security and pensions law. My complaint still stands in, that I am legally a woman and not a man as the United Kingdom would so wish me to be. Again they have cited the Cossey case, and again I

15. state, that this case is of no avail in my case. My legally given sex status by a court of law, within a parliamentary Act takes precedence over case law.

All social security benefits and state pension schemes here in the Netherlands regard me as legally a woman and not a man. Neither would any other country within the European Communities regard me as any other, except the United Kingdom. In this they are directly interfering in my legal status.

20. The use of para 26 in the Cossey judgement was used by the court, only because, the court had been mislead by the United Kingdom regarding the Corbett case. The judgement by Ormrod in that he purported he had been called upon for the first time in English law to define a person's legal sex. This was not true he had only been asked to declare the marriage null and void because the respondent at the time at the marriage was of the male sex. Which was true, in that the birth certificate had never been amended neither had the respondent been able to show otherwise. By going into the alternative Ormrod broke the Rules of the Supreme Court thereby making his judgement void. But it can be seen what the far reaching consequences of his judgement meant, and that his judgement gave powers to the public that they did not have before, these powers being discriminatory. This is what Ormrod said; "In some contractual relationships e.g. life assurance and Pension schemes, sex is a relevant factor in determining the rate of premium or contributions". And further on he said. There is nothing to prevent the parties to a contract of Insurance or Pension schemes from agreeing that the person concerned should be treated as a man or a woman, as the case may be. Similarly the authorities if they think fit, can agree with the individual that he shall be treated as a woman for National Insurance purposes, as in this case".

If for example the United Kingdom were to use such a rule for the purposes of determining the rate of premiums for a migrant worker from the European Communities who was in the same position as me they would be held in contravention of community Law. Such an act would be questioned by the Government from where the migrant worker came from. That the United Kingdom is refusing to recognise a person's legal sex.

It is quite clear that the United Kingdom, are, failing to recognise my legal sex status.

21.Para 2.9. The statement by the United Kingdom here has already been dealt with in para; 20. It is not necessary for any insurance company to deal with anything other than the information that is given. That I am a legally a woman is seen in my amended birth certificate, a short form of my birth certificate is enough for any insurance company, which shows no more than the information as to my legal status as a woman. Anything other is private and of no concern to anyone else. In the Netherlands all that is necessary to show employers insurance companies etc, if required, is a document that shows only a persons present status. The only time when more information is required about a person, say be for specific types of work, e.g. where a person may apply for a position that would involve

16.

Children, then a research is carried out on that person to be assured that the person has no convictions for child offences. Even then if it is seen that the person was originally recorded as male is treated as of no concern to the researchers as that information is private, and remains so and would not be disclosed to anyone else.

The United Kingdom have, already stated themselves that the information concerning the individuals who had their birth certificates amended is confidential, and that they have not consented to disclosure. (see para. 2.5) The same applies to me, as I have an amended birth certificate. Anything other than that is interference, in my personal life.

22. Concerning their contentions as to whether I have a criminal record. When such an amendment to a person's birth

certificate, is made, then a person has it made clear to them from the beginning , that such an amendment implies no derogation from previous commitments, that includes facts such as a criminal record.

Again I see their statement as implying that they have a right to disregard my legal status and interfere in my private life.

23.The last two lines of 2.9 of the UKs observations concerning, "whether or not I as the Applicant wish to deal with a company, regarding Insurance and Pensions on the terms as set down by the British Government" shows clearly the lack of recognition of somebody’s sex/gender identity. In my case it was not acquired, because that gender identity was always there, it took time and some medical interventions to make the nature of it apparent (visible). The problem is not whether I am willing (or not) to accept the terms of a company. But the problem as whether a company is legally free to set terms/to use practice which results in discrimination of one woman (me) compared to others. It is NOT the freedom of a State Party to the European Convention to allow companies in its territory to apply discriminatory rules/practices. As I am legally a woman I should be treated like all other women. The use of a birth certificate, - that as the UK states "only presents an historical fact" - should and cannot be used for present judgements/practice when that certificate - the unamended version in the United Kingdom - is clearly wrong, as in my case. (see Prof. Gooren's statements cited in my observations).

17.

PART III ADMISSIBILITY AND MERITS

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

Before giving my more specific comments on the observations of the UK Government I would like to state the following.

As far as the merits of my case are concerned, I like to join the dissenting opinion of Judge Maartens in the Cossey case. He has - much better than I can do, as not fully educated in human rights law - argued why the Rees case should have been decided differently and why this decision should have been overruled in the Cossey case. I like to have this legal argument considered as mine judging the merits of my case.

Indeed, the essence of my complaints is that the UK Government denies the full legal recognition of who I am and always have been; a woman. In that regard I like to refer to Judge Maartens opinion in the Cossey Judgement under 2.7, and make the following observation. Judge Maartens, argued on the basis of a person’s freedom to shape himself and his fate in the way that he deems best fits his personality and says; "the (transsexual) demands to be recognised and to be treated by the law as a member of the sex he has won".

My main and most important argument based on the scientific research I presented in this document (see para 4, p. 2 - 7) is: I want full legal recognition of the person I am and I always have been, that is a person with a female gender/sex identity. The gender identity given to me at birth based on external genitalia was wrong. It turned out that that I was one of the very few persons for whom the usual way of sex assignment (based on external genitalia) was not reliable because the sexual differentiation process of the brain did not follow the course anticipated on the base of the external genitalia.

It as a fundamental human right to be fully, legally and socially, recognised as the person I am and always was, a person of female (gender/sex) identity. It is that right that the government of my country denies me.

My more specific observations should be seen in the light of this fundamental violation of my rights under the European Convention of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedom (in particular: art. 3, 8, 12 and 14).

1. Para. 3.4. The United Kingdom declares that. Contracting States are not required to recognise, for legal purposes, the new sexual identity of a person who has undergone gender reassignment surgery. Praying on the Cossey judgement para 40 and B v France, and from this that I have no legal right to recognition as a woman, and that Contracting State have a wide margin of appreciation.

2. Contracting states are required to recognise a persons legal sexual identity, when that identity has been medically and certified and recognised, as in my case, and by a court of law, and that the persons birth certificate must be amended to show this to be so. Which has been done, in that a new birth certificate

18.

Had to be made, done under due process of law.

3. The use of the Cossey Judgement para 40 by the United Kingdom is of no avail in my case. That judgement was based on the Rees judgement. Neither had the Court been given the full truth by the United Kingdom, in that the plaintiff Rees did have the right for an amendment on his birth certificate under section 29 of the Births and Deaths Act, so did the plaintiff Cossey.

The statement by the Court that no scientific developments had occurred in this field is also not true. They were relying solely on such contentions by the United Kingdom, who have not attempted to make such research, but rely solely on an invalid judgement in the Corbett case.

Also in that paragraph is mentioned the European Parliament Resolution 1117of 12 September 1989 and Recommendation 1117 of 29 September 1989. Stating that both were to seek the harmonisation of laws and practices in this field.

This is not really true. The European Parliamentary Resolution was designed only for states who were deficient within their Legal practices, concerning transsexuals, and that such states would discuss this matter within their own parliament, to remedy the situation, and accord to these people their legal rights. For countries, that had already remedied the situation within their legal practices, the Resolution had no meanings. In this manner the resolution was meant for such countries as the United Kingdom, who chose to ignore it, on the grounds that such Resolution were not binding, which showed contempt for the European Community.

Recommendation 1117 of the Council of Europe, was a recognition of what was contained within the Parliamentary Resolution. That States who reneged on their duties to recognise a transsexuals legal status fully, regarding treatment, change of the persons legal sex status on birth certificates and identity documents was a breach of Art 14 of the Convention.

The resolution and the recommendation were not as was stated to seek harmonisation of laws and practices.

The statement also that States enjoyed a wide margin of appreciation due to little common ground between them, has no meaning any more, as European Community States have closed this gap.

This was agreed upon at the 23rd Colloquy of Medicine European Law and Transsexualism, at the Free University of Amsterdam in 1993. Also at this conference was produced the research evidence from the Gender Centre at the Free University Hospital of Amsterdam, that showed conclusively that a persons sex could not be determined at birth. Throughout the whole conference representatives of the United Kingdom Government attended only two days, neither did the United Kingdom show any Research evidence to dispute the evidence shown, as they had none. At the end of the first part of the conference, it was concluded that the medical evidence was agreed upon. And so was it agreed that countries who were members of the Council of Europe, and countries outside of the Council, would recognise the validity of a transsexuals legally amended sex status. That where practices within each state differed and how they made, this legal change other countries would accept the result.

19.

It was then asked if there was any dissension, there was none. Even the United Kingdom did not show dissent to this agreement. Therefore it must be asked, where is this wide margin of appreciation? The answer is, there is none.

4. The use of B v France in this case again is of no avail. It is a case that has no relation to this case. In that case B had demanded through the civil Courts in France that her name be legally changed, on her birth certificate, which under French law was possible. But this had been refused to her on the grounds that she had undergone corrective surgery in another country. Where it was also stated that there were existing possibilities in France, which included legal safeguards, but she had been denied proper treatment in France, which was why she had gone to another country for required surgery.

The French Government prayed upon the Court that the Rees and Cossey cases were similar to the case of B, and that the Court should hold the same view concerning the birth certificate. In the end it was refused and the Judgement given in favour of B.

The statement para 48 of the Judgement in the case of B says at one point, "that there still is uncertainty as to the essential nature at transsexualism". That is now already known and was revealed at the 23rd Colloquy, and can be seen on p. 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7of this document. The judgement on the case of B was given in 1992, which was before the Colloquy in 1993.

5. Para 3.5 Concerning whether the States treatment of a transsexual amounts to a positive obligation under Art. 8., and a fair balance between the individual and the community, and detriment suffered by the applicant. Again using Cossey Judgement and B v France Judgement.

Again neither of these two cases are of any avail in my case. As the applicant in this case I am legally a woman, which the United Kingdom refuses to recognise, but have given no legitimate reasons as to why they are prepared to interfere in my private life by not recognising the fait accompli on my part. I am seen as a woman, legally by the community in the Netherlands and other countries, and accepted as so, neither are other people aware of me being anything other. In this respect there is nothing of an unfair balance between me, and the community. The only unfairness in this situation is the United Kingdoms refusal to recognise my legal status.

6. Para 3.6 The United Kingdom is attempting to use the Cossey and the B v France Judgements again. In saying that the court concluded in the Cossey case that there had been no breach of Art 8 in refusing to issue the applicant with a new birth certificate showing her sex after surgery.

As I have shown on page 10 para; 11 in this document the plaintiff Cossey did have a right for her birth certificate to be changed under Sec. 29 CORRECTION OF ERRORS IN REGISTERS.

It was only by the misleading statements concerning such changes, to the court, in both the Rees and Cossey cases that such a judgement came about.

20.

7. The use of B v France in this case is of no avail. Where the United Kingdom state, that the Court explained the difference in that case to the Cossey and Rees case. Which was based on the contention that the birth certificate in the United Kingdom was a historical document as opposed to France where such a certificate was intended to record current facts only, came about from the misleading information that the United Kingdom gave to the Court.

The Births and Deaths Act in the United Kingdom is not a historical document. It is a Register to register the facts of a birth or a death, subject to changes where they are necessary, but the original facts may not be erased, they can be amended, any amendment taking legal precedence over the original inscription. As I have already shown on page 10 of this document.

The same principles applied in the Netherlands, and an Act of Parliament made it possible for such changes to be made in the Birth Act.

The United Kingdom could make an amendment to the Birth Act whereby they could deny a person of transsexual birth the right to amend the birth certificate under the existing section 29, but to do so would be seen as a direct infringement of the European Convention of Human Rights.

7. I see no base for the contentions of the United Kingdom in para; .3.6.

8. In para 3.7 The United Kingdom state that none of the complaints I have made in my case establish a degree of practical detriment to my private life.

I see here that the United Kingdom believe that they have the right to deny me my legality as a woman, and the legality of my new birth certificate, but at the same time state that I can live free from state interference. At the same time, state further, that on rare occasions I am obliged to reveal the sex I was born into for good reasons.

The sex that was placed on my birth certificate was by the hand of a person that took it for granted, that I was male. The reality at my real sex came about four years later. I was not really born into the male sex as is contended by the United Kingdom, but transsexual or inter-sex.

The only State interference in this matter is by the United Kingdom and they have given no accountable reason as to why they should. The truth is that they know that in two previous cases to Strasbourg they did not tell the truth and were given a judgement in their favour, that was in detriment to the human rights of Rees and Cossey. One of those two people, the plaintiff Cossey, has found that she has had to leave the United Kingdom and live in the United States of America, where her rights as a woman are respected. But even then now she is married the spectre of the birth certificate, which the United Kingdom denied her the legal right she had, to amend it, is still there. This shows how far the interference of the United Kingdom has gone in regards to her private life. They are trying to do exactly the same to me, only in my case I have a legally amended birth certificate, but still they will interfere in my private life by stating that they will not recognise it.

21.

I do not have to reveal for any legitimate reasons what was inscribed originally in the birth registers. It is only necessary to reveal that i am a woman and nothing else. Why should I. I am legally a woman.

9. Para; 3.8 There, is little to answer on the statements in this paragraph that have not already been answered. As I have stated before IT IS POSSIBLE to amend the birth certificate in the United Kingdom in the case of a person who was born a transsexual, which cannot be seen at birth, but only later in life. Again the Judgement that was given in the Cossey case was based on misleading given to the Court, by the United Kingdom. Neither as I have stated before is the birth certificate a historical record of facts, it is a document subject to changes as laid down in the Births and Deaths Act of 1953.

10. Para; 3.9 The statements as laid down in this paragraph, are in detriment to my private life, and constitute an infringement of Art 8.of the Convention. The United Kingdom is not entitled to regard me as a man for the purposes of the law of marriage nor for any other purpose because I am not a man and have never been a man. To consider me as a man on the basis of my external genitalia was - in my case - wrong ("see my general observations")

My legality, as a woman was qualified by medical findings and recognised within the law, as laid down in the Civil Code of the Netherlands. The United kingdom have no right to attempt to take that legal status away from me, or attempt to interfere in any way. The United kingdom are obliged to recognise my status as a woman for all legal purposes, including marriage, social security and pension laws. They are also obligated under section 29 of the 1953 Births and Deaths Act to inscribe an amendment in the Births Registers to this fact.

11. Para; 3.10 The United Kingdom are fully aware of the medical research findings that were shown at the 23rd Colloquy of European Law medicine and Transexualism, in that they had representatives present at the conference. Neither did those representatives give any sign of dissent when all the participants were asked if there was any disagreement to the findings at that conference. I was at that conference, and at the end of the first part, I personally asked the representative for the Home office if there would from that point be any change in the attitude of the United Kingdom. The answer I was given, that in their opinion there were no changes, neither would there be any changes in the position of the United Kingdom, on this matter. Neither was the United Kingdom able to show any research evidence contrary to the research evidence shown. Again I accuse the United Kingdom of trying to mislead the Court on this matter.

12.para 3.13 The contention of the United Kingdom that they are not in breach of Art .14 of the Convention in that they are trying to incorporate breaches at Art 8 cannot be accepted.

22.

Art 14 has total different meanings in this respect as in comparison to Art 8.

In my case the United Kingdom have breached Art 8 in respect to my private life concerning my birth certificate, in that they have clearly stated that they are prepared to interfere in my private life.

Art 14 in this case involves the refusal by the United Kingdom to respect Recommendation 1117. Which clearly demands legal recognition of a transsexual, and above all that the sex of a person must be respected, and birth status. In this case they refuse to recognise my true birth and sex status as is now already recorded on my new birth certificate. As opposed to Art 8 where they are prepared to interfere in my private life, for which they have not shown any valid reason to do so.

I contend that they are in breach of Art 14 to my detriment.

13 para 3.14 Concerning Art 12 at the Convention. The United Kingdom, use the judgement of the Cossey and the Rees case as an example as to why I do not have the right to marry a man. It must be remembered that the judgement in the Cossey case was based on the Rees case, it must also be remembered that the findings of the Commission in the Cossey case were opposite to that of the High Court, as can be seen in para 43 to 41, where the Commission stated, 43. The Commission now considers that marriage and the foundation of a family are particular events in the life of an individual which go beyond the mere realisation of private and family life as they involve two persons who form a legally and socially recognised union which creates both responsibilities and privileges. Article 12 of the Convention therefore guarantees a specific and distinctive right of an independent nature as compared with the right to protection of private and family life guaranteed by Article 8 para.1of the Convention.

In fact the distinction between Articles 8 and 12 must be seen essentially as a difference between the protection under

Article 8 of de facto family life irrespective of its legal status (cf Eur. Court H.R., Marckx judgement. of 13.6.1979,

Airey judgement of 9 10 1979 and Johnston judgement of 18 12 l986, series A Nos. 31, 32 and 112) and the right under Article 12 for two persons of opposite sex to be united in a formal, legally recognised union.

Therefore, the finding that there has been no violation at Article 8 of the Convention does not automatically exclude the finding at a violation of Article 12.

44. As far as the present applicant's right to marry is concerned. The Commission first observes that her application contains a factual element which distinguishes it from the Rees case and the other transsexual cases so far considered, in that the present applicant has, according to her uncontested statements, a male partner wishing to marry her.

45. The Commission agrees, in principle, with the court that Article 12 refers to the traditional marriage between persons of opposite biological sex.

23.

It cannot, however be inferred from Article 12 that capacity to procreate is a necessary requirement for the right in question. Men or women, who are unable to have children enjoy the right to marry just as other persons. Therefore, biological sex cannot for the purpose of Article 12 be related to the capacity to procreate.

46 It is certified by a medical expert that the applicant is anatomically no longer of the male sex. She has been living after gender reassignment surgery as a woman and is socially accepted as such.

In these circumstances it cannot, in the Commission’s Opinion, be maintained that for the purpose of Article 12 the applicant still has to be considered as being of male sex. The applicant must therefore have the right to conclude a marriage recognised by the United Kingdom law with the man she has chosen to be her husband.

14. The United Kingdoms contentions that certain cases named as, X Y and Z v United Kingdom. Which were apparently dismissed by the Commission on the 1st of December 1994 as being manifestly ill-founded that Article 12 conferred a right for a transsexual to marry a person of the same sex as the transsexual had at birth. Bears little relation to my case and my legal status.

I am legally a woman, and I have the legal right as a woman to marry any man I choose to marry and who wishes to marry me. The law giving protection to my rights as a woman concerning divorce and alimony. The United Kingdom, have no right to even attempt to ever deny me such rights, to do so would be to hold law in contempt, and human rights.

15. Para: 3.17 The United Kingdom denies that their actions concerning me have violated Art 3. I contend that they have and still contend that their actions amount to mental cruelty, and that they will continue to so by denying me my legal status, and interfering in my private life. Their actions have also placed me in the peculiar position of not being able to return to my own country to enjoy my legal status as a woman.

Their actions have also placed me in the position of not being able to use my British passport as a travel document They refuse to recognise my legal status as a woman and would interfere in my private life where I may have to produce my English birth certificate. My only alternative is to use my Netherlands nationality, and even then on entering the United Kingdom I have to do so as a foreigner in my own country. Even then they still refuse to recognise my legal status as a woman.

Their actions amount to mental cruelty, which they refuse to desist from.

Their use of the B v France case in this respect is of no avail here, considering the report of the Commission of that case at para 76 - 87. In that case they have looked at the meaning of Art 3 in the light of Ireland v United Kingdom and the Soering judgement. Both of those cases have no resemblance to mine. In Ireland v United Kingdom this was a case of premeditated torture used against members of the IRA.

24.

Torture and degrading treatment and punishment inflicted upon a prisoner can go hand in hand. The Soering judgement on the other hand involved a person who was arrested for a bizarre murder that he committed in the State of Virginia in the United States of America, and that he was arrested in England. The government of the United Kingdom consented to the demand of extradition from the United States of America. Disregarding the consequences that he would receive the death sentence, and the long wait in death row, and the methods used in the United States to execute people. Considering also his age, which was 18 years and his mental state. It was decided by the Court, that for the United Kingdom to carry out the extradition would be a breach of Art 3. It is clear that both the Ireland v United Kingdom cases and the Soering case were both of a different nature to each other, and the Commission attempted to define; what constitutes a breach at Art 3 in B v France in relation to those two cases. There was none.

Looking at Art 3 and its wording; "No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment." It cannot be held that it has only one particular meaning. Torture and degrading treatment or punishment are not necessarily one act together. A person can be treated in a degrading manner and not necessarily physically tortured or punished. But the end result of degrading treatment can cause mental distress that can be described as mental cruelty. A wife who is constantly being beaten by her husband is degrading treatment resulting in mental stress and mental cruelty. A person who is persistently denied their human and legal rights by a government, resulting in public scrutiny, and social denial of their rights, is mental cruelty, which is degrading treatment. In this respect the United Kingdom are guilty of this act in respect to my legal and social rights.

I uphold my contention that they are in breach of Art 3 in this respect.

16. Para; 3.18 - 3.20, Concerning Protocol 4 art 3. The United Kingdom is correct in stating that they have not ratified Protocol 4. Since my accusations against them that their actions in refusing to recognise my legal status as a woman, deprive me of the right to enjoy my legal status on entering the United Kingdom, that this is a form of expulsion from my own country. I still contend the use of this Article here, even though I am aware that they have not ratified it, is to show the extent of my position. But if the Commission care to look again at the documents that I sent to them on the 3rd of December 1993 it will be seen that I covered all the Articles I had used, to go under Art 17, under conclusions. Where it reads; "by refusing to recognise my legal status as a woman in my own country of origin and birth and as such are aiming to destroy my rights and freedoms as set down in the Convention".

Article 17 of the Convention states: "Nothing in this convention may be interpreted as implying for any State, group, or persons, any right to engage in any activity or perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein or at their limitation to a greater extent than is provided for in the Convention".

25.

My contentions that they have refused to recognise my legal status on entering the United Kingdom, amount to a form of expulsion, are aiming to destroy my rights and freedoms as set down in the Convention.

CONCLUSIONS

The United Kingdom has clearly shown that they have no intentions of coming to terms with my legal status as a woman. Neither have they shown any willingness to keep abreast with scientific/medical research and findings on the issues here, but to keep an outdated medical demand that was made by a judge in a divorce case, Corbett v Corbett, judgement by Ormrod.J. I have already pointed out that the judgement of that divorce case has no legal validity, because he broke the Rules of the Supreme Court RSC in English law. The fact that under the English Constitution, a judge does not have the right to dictate to Parliament what the laws at the land should be, as its constitution is a Parliamentary Democracy, which prescribe the laws of the land, which governs the rules of the courts, and the judges. Neither does a judge have the right to dictate what amendments should be added to the law. It can quite clearly be seen in the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 where an amendment was made to the Act sect; 11 para.c. "that the parties are not respectively male and female". This provision came about from the demands made by judge Ormrod in the Corbett case. The UK Government by adding such an amendment from such a judgement broke the rules of their own constitution, as the amendment was a directive from a judge, not from an unbiased parliamentary debate. The UK government is aware of the scientific facts that I have presented in my case, and have been since 1993 at the 23rd Colloquy of European Law Transsexualism and Medicine that was convened here in Amsterdam.My legality as a woman has clearly been shown by documented evidence.

I repeat that they have clearly shown that they are guilty of having contravened my rights under the Articles of the Convention as I have presented to the Commission, and will wilfully continue to do so.

Neither is there any alternative in their conclusions para.4.l in their declaration that my application ill founded and that if declared admissible that there has been no breach of the Convention by the United Kingdom. Which shows that they are not prepared to accept mediation by the Commission. Therefore this case must go forward to the High Court for a judgement.

My application is, well founded, well documented, and clearly showing my legal status that they deny. I demand that. Since they wilfully refuse to accept my legal status as a woman and accord to me all the rights that I am entitled to, under that legal status, that they must pay me financial compensation for mental cruelty and all the costs that they are now responsible for. Which have been incurred by my having to bring this case to the Commission.

I demand that the Commission find the United Kingdom to be

26.

Held in breach of having violated my human and legal rights in this affair.

Signed this day 17 - February - 1995

By. Rachel Horsham. Plaintiff.

(Note. The original hand written statement from Professor Gooren concerning the scientific findings of the Stria terminalis, presented with this document, can be seen in Gif image No. 85 on the index page. The letter from Professor Gooren stating that all the medical evidence presented is correct, can be seen on Gif image No. 86.)

BIRTHS AND DEATHS REGISTRATION ACT 1953

723

PART

IIREGISTRATION OF DEATHS

15 Particulars of deaths to be registered . . . . . . . . . 738

16 Information concerning death in a house . . . . . . . 739

17 Information concerning other deaths . . . . . . . . . 740

18 Notice preliminary to information of death. . . . . . . . 741

19 Registrar’s power to require information concerning death . . . . . 741

20 Registration of death free of charge . . . . . . . . . 742

21 Registration of death after twelve months . . . . . . . . 742

22 Certificates of cause of death . . . . . . . . . . . 743

23 Furnishing of information by coroner . . . . . . . . . 744

24 Certificates as to registration of death . . . . . . . . . 744

PART Ill

GENERAL

Registers, certified copies, etc

25 Provision of registers, etc, by Registrar General . . . . . . 746

26 Quarterly returns to be made by registrar to superintendent registrar . . 746

27 Quarterly returns by superintendent registrar to Registrar General . . 747

28 Custody of registers, etc . . . 747

29 Correction of errors in registers . . . . 748

Searches and certificates

30 Searches of indexes kept by Registrar General . . . . 749

31 Searches of indexes kept by superintendent registrars . . . . 750

32 Searches in registers kept by registrars . . . . . 751

33 Short certificate of birth . . . . . . 751

34 Entry in register as evidence of birth or death . . . . 752

Offences

35 Offences relating to registers . . . . . . . 754

36 Penalties for failure to give information, etc . . . . . 754

37 Penalty for forging certificate, etc . . . . . . . . 755

38 Prosecution of offences and application of fines . . . . . . 755

Miscellaneous

39 Regulations . . . . . . . . . 756

40 Sending documents by post . . 756

41 Interpretation. . . . . . . 757

42 Savings,etc . . . . . . . 758

43 Repeals and consequential amendments . . . . . . . 758

44 Short title, extent and commencement . . . . . . . 759

SCHEDULES:

First Schedule—Consequential Amendments of other Enactments. . 759